(Or, why the status of Confederate flags as symbols of Southern-ness must be challenged)

The South needs a new flag. The emblems most commonly associated with the region at present are also emblems of the Confederacy – and therefore, by extension, of white supremacy – but the geographical and cultural area thought of as the Southern United States need not be associated with either of those concepts. Indeed, if its existence is to be ethical, those who believe in the validity of the South as a construct, and who espouse Southernness as a facet of their identity, must extinguish its association with both the Confederacy and with white supremacy, embracing instead a Southernness which is not only overtly and avowedly multi-ethnic and anti-racist, but fully intersectional with all facets of the cause of social justice, from minority language revitalization and anti-capitalism, to feminism and LGBTQIA+ activism.

The promotion of a Southern identity is not only compatible with, but complementary to, these ideals: Southerners, albeit it to a lesser extent than members of the oppressed groups whose causes are outlined above, are themselves no strangers to oppression. Many have been forced by prejudicial employers to disguise their accents or else look elsewhere for work; mocked and derided by strangers or even friends as ignorant, inbred, and irremediably unsophisticated; or assumed, based only on their place of origin, to be culturally inferior to people from elsewhere in the English-speaking world. This regional prejudice – rooted, like the Southern identity itself, in the nexus of culture and geography – ought to be answered by the affirmation of a Southernness with positive attributes: a Southernness of loving-kindness and respect toward all people, clarity and vigor of thought, and justified pride in knowing and developing the cultural traditions of the region. It is hoped that the flag proposed in this document might serve as the banner of that affirmation.

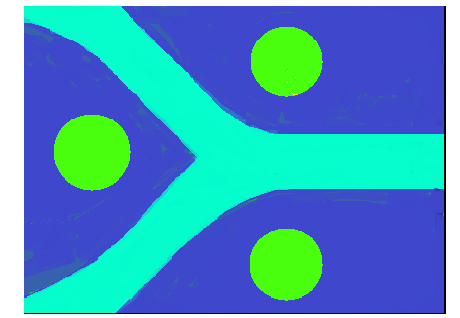

The proposed flag – loosely representing a map of the Southern United States (as oriented to the East, instead of the North, in Gaelic fashion – consists of a spring-green field, divided into three sections by three broad, curving, aquamarine or turquoise lines. The horizontal line, extending inward from the center of the right edge of the flag, represents the Lower Mississippi River (that portion of the Mississippi River that lies downstream of its confluence with the Ohio). The lower blue line, ascending from the bottom-left corner of the flag, represents the Upper Mississippi River (that portion of the river that lies upstream of the Ohio confluence). The remaining line, descending from the top-left corner of the flag, represents the Ohio River itself.

The resulting three fields represent the three regions which arguably constitute the geographical domain of Southern culture: to the southwest, represented by the lower field of the flag, lies the trans-Mississippian South of western Louisiana, eastern Texas, eastern Oklahoma, Arkansas, southern Missouri, and southern Illinois; to the northeast, represented by the semi-triangular left field of the flag, lies the trans-Ohioan or ‘Butternut’ South of southern Indiana, southern Ohio, West Virginia, and Appalachian Pennsylvania; and, to the southeast, represented by the upper field of flag, lie the Deep South, the Upper South (also called the Trans-Appalachian South), the piedmont and tidewater regions of Virginia and North Carolina, and the central and southernmost segments of Appalachia.

In each dark blue field resides a spring-green circle representing one of the three indigenous Southern fruits that give the flag its bynames: the pawpaw, the persimmon, and the mayhaw. The stylized depictions of the fruits are spring-green in color in recognition of the fact that each of the three exhibits such a hue at some stage in its ripening process.

The choice of these fruits as symbols of Southernness rests on the basis that two of them – the pawpaw and the persimmon – grow throughout the region generally thought of as the South, although the former’s range slightly exceeds the geographic boundaries of the South to the north and the west. This serves as a reminder that the idea of the South – despite its rootedness in geography – has not the definite geographical boundaries of a nation-state, and defies strict delineation. The third fruit, the mayhaw – though it grows only in the Deep South – represents a distinct cultural and ecological commodity of the South by the very virtue of the limitedness of its range, and therefore serves as a reminder that the South itself, although united by various cultural continuities, nonetheless exhibits tremendous internal diversity.

The pawpaw, the mayhaw and the persimmon are the only native arboreal fruits that grow north of Central America – or at least the only such fruits thought of as edible by human beings. In their uniqueness, they symbolize the regional distinctness of the South; and – importantly – in their indigeneity to North America, they serve as a reminder that the land beneath the feet of modern Southerners once belonged solely to indigenous peoples. Only by acknowledging this fact, and by doing justice to the living representatives of the people from whom the land was unjustly taken, can any modern Southerners – especially those descended from European colonists – ethically steward Southern lands today.

The triplicate pattern formed by the fruit obliquely pays homage to the awen – a symbol developed by the Welsh nationalist Yolo Morganawg in the early days of the Celtic Revival. He professed a belief that the symbol was of ancient ‘druidic’ origin, when – in fact – he probably invented it himself. It features on the flag as both a celebration of Welsh culture, which has played an important but often overlooked role in the colonial history of the South (legend has it, after all, that the medieval Welsh prince Madog was the first European to travel West of the Allegheny mountains); and as a reminder that it is both possible and legitimate for members of a given culture to creatively reinvent that culture in service to a worthy cause.

The colors of the fruit – and of the flag in general – are highly symbolic. In the Goidelic languages – that is, Manx, Irish and Scottish Gaelic – whose speakers played an important role, for good and ill, in the cultural foundation of the modern South, the word for dark blue or dark green (in Scottish Gaelic, gorm) historically meant ‘Black’ in the context of human skin color. Therefore, the fact that the blue swathes of the fields define the shape of the flag symbolizes the fact that Black people – in terms of their presence in, their achievements on, and their connection to Southern lands, and their oppression and willful omission from Southern history by self-identifying ‘whites’ who have sought to control the South and its people for their own gain – have helped to define what the South is, and will continue to play an important role in shaping what it is to become. The spring-green color of the fruit – placed in such close proximity to the blue fields and sea-green rivers – serves to remind us that Black Southerners, despite their forced labor as slaves and convicts, have found in their cultural inheritance and collective ingenuity an inspiring capacity for perennial self renewal. Only by acknowledging the legacy of race based oppression, and the collective resilience of the Black people people from whom freedom was unjustly taken, and yet who have survived in, thrived in, and in no small measure culturally defined the South, can the Southern region and its peoples come to terms with the many dehumanizing acts of white-supremacism which have been committed in its name.

Thus, colors of the flag are spring-green (in Gaelic, uaine), dark blue (in Gaelic gorm), and sea-green or aquamarine (in Gaelic, glas). In terms of geographic, ecological and ideological symbolism, the first color symbolizes the hope of societal, cultural, and ecological renewal. The second color (which, in Gaelic, compasses not only dark blue, but dark green) symbolizes the green fields and woodlands of the South – once and still so dear to the Southern people, especially indigenous Southerners – and embodies the Southern hope for an environmentally sustainable future for its lush woodlands and meadows despite the intensifying ravages of climate change; the Black bodies callously broken to build the society that now encroaches upon those woodlands and meadows; and the Black communities that have defined what the South is, and what it may yet become. The third color represents the life-giving waters of the rivers, lakes, and aquiphers – so abundant in biodiversity – that form the arteries of many a Southern community’s transport infrastructure; and the the carrying stream of living tradition that will bear those communities’ worthiest and most cherished lifeways into the future. Yellow, the color of the ill-gotten gold of the tainted white-supremacist past, will be omitted from the flag. White – the color of racial whiteness, a false consciousness which has debased all those who subscribe to it, divided workers against their corporate masters, and served as the millstone beneath which the hopes and dreams of tens of generations of innocent people have been ground to dust – will likewise be omitted. Ours is not the flag of the white race, nor is it the flag of surrender. Red – the color of blood, rage, and fire – will likewise be omitted, in the sincere hope that, though there can be no peace without justice, we may yet live peaceably by seeing that justice is done.

In their triplicate number, the three spring-green fruits, the three azure fields, and the three aquamarine rivers also represent the three core Southern virtues: generosity (as seen in the bounty promised annually in the green shoots and leaves of the spring), conviviality (as demonstrated by the diversity of living things in the fields and forests who, despite or even because of their differences, exist for what is ultimately their mutual benefit), and community (as symbolized by the aquamarine rivers and the interconnectedness they once afforded rural communities in their role as the South’s first great highways). Southern culture is famed for its generosity, as illustrated by the celebrated quality of ‘Southern hospitality’. Southerners, at their best, give freely of their possessions even when they have little, and do as best they can to help people in need; they are generous not only with their possessions, but with their time – volunteering it for the benefit of loved ones and even strangers, and not losing patience even when their patience is tried. The need for Southern generosity is greater than ever before. The South has always been a hospitable land, and will appear yet more so as climate change makes other lands less and less hospitable. When the rivers and aquifers of the West run dry, and the coastal cities sink beneath the rising seas, their people will seek refuge among us, blessed as we are with ample water and as-yet-un-inundated highlands. Then, more than ever, will be the time for Southern generosity; for if, in that moment, we hoard our wealth, we will have made ourselves unworthy to possess it. Let us hope, that – in their gratitude – the incomers will adopt the lifeways of the South, so that those elements of our culture that we rightly cherish will go on unchanged. If we seek that outcome, then we must teach by example, and show our cultural practices to be worthy of imitation.

Southern culture is famed for its conviviality, or courtesy, as illustrated by the celebrated quality of ‘Southern charm’. Southerners, at their best, are kind and sociable; able to compliment freely but without insincerity, and to criticize without incivility; good humored, even in the midst of hardship; and companionable, even in the company of people whom they scarcely know, and by whom they in no way stand to profit. When Southerners have failed in the exercise of this virtue, the results have been calamitous. Truly, no courtesy was shown by European settler-colonists to the people of the First Nations; or by masters and overseers to their slaves; or by fearful and entitled white Southerners to the civil rights activists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Now is the time to redress those wrongs, and – in doing so – to redouble the Southern commitment to courtesy, not only insofar as nicety (which, while pleasant, can be superficial) but in terms of true loving-kindness and compassion. Courtesy, in its amplest sense, entails the implicit recognition of the personhood of all people in striving to make them feel comforted and esteemed, and neither oppressed nor even oppressor will live in true comfort or sincere high self-regard until the systems of oppression that ensnare them are unmade, and equality established in their wake. Courtesy, in this sense of the word, means the good treatment of all people, even when to do so comes inconveniently, or at the expense of one’s own privilege – and it is to this sort of courtesy which Southerners must now aspire.

Southern culture is famed for is sense of community, as illustrated – for better and for worse – by the stereotype of the small Southern town: there, everyone knows everyone else, and everyone else’s business; and secrets are hard to keep, but not so traditions. Such interdependence, inter-reliance, and social inertia has its dark side: many a would-be member of the LBTQ+ community has died without having ever fully lived, for fear of condemnation by a Southern community. Their often un-told stories, and stories like them, ought never to have played out as they did, and must not be forgotten. We should also bear in mind, however, that close-knit communities have been the salvation of many a Southerner in time of want, and that so many evils of the Western world have come from the sundering of the bonds of family and friendship. Human beings are social creatures, inclined by nature to commune with and help one another; if isolation is, as mounting evidence suggests, lethal to us, then the modern United States – with its ethos of the rugged individual, the nuclear family, and the independent consumer – is little short of a killing machine, even among its own citizens. The South – often lampooned for its rurality – is one of the regions of the US where older models of community have not entirely surrendered to the neoliberal onslaught, and where, even if diminished, they stand the best chance of revival.

If we direct the course of the enterprise of our stateless nation-building in accordance with these virtues, we might yet redeem the South in the eyes of those whom she has wronged, and exalt her reputation in the eyes of those who have heretofore looked on her with contempt.

This new Southern flag – to be called the Pawpaw Flag, the Mayhaw Flag, the Persimmon Flag, or simply the Flag of the South (Bratach an Deas, in Scottish Gaelic) – will hopefully help contribute to the symbolic repertoire of the leftist Southern cultural revival to come.